Creating functions#

At this point, we’ve seen that code can have Python make decisions about what it sees in our data, and we’ve used loops to repeat operations on multiple items. But what if we need to build more complex calculations, and use them in multiple places?

As always, let’s start by making sure our data is load and libraries are imported:

import numpy

import matplotlib.pyplot as plt

traffic_data = numpy.loadtxt('traffic_data.txt', delimiter=',')

For example, let’s say we want to calculate what percentage of daily traffic occurs during rush hour (7am to 9am). This calculation needs two pieces: the rush hour traffic total and the total daily traffic. We might write it like this:

day = traffic_data[0]

rush_hour_total = day[7] + day[8] + day[9]

daily_total = numpy.sum(day)

percentage = (rush_hour_total / daily_total) * 100

print('Day 1 rush hour was', percentage, 'percent of all traffic')

Day 1 rush hour was 8.931416634210247 percent of all traffic

This is fine, but it’s a bit hard to read and understand quickly. And imagine if we needed to do this calculation in multiple places throughout our codebase. If we later decide to change how rush hour is calculated, we’d have to update it in multiple places. This is annoying at best, and at worst might lead to bugs if we forget to update somewhere.

We can solve all these problems by wrapping this calculation in a function:

def rush_hour_percentage(day):

rush_hour_total = day[7] + day[8] + day[9]

daily_total = numpy.sum(day)

return (rush_hour_total / daily_total) * 100

Now our code gets much simpler:

print('Day 1 rush hour was', rush_hour_percentage(traffic_data[0]), 'percent of daily traffic')

Day 1 rush hour was 8.931416634210247 percent of daily traffic

A function definition opens with the keyword def followed by the name of the

function (rush_hour_percentage) and a parenthesized list of parameter names

(day_data). The body of the function—the

statements that are executed when it runs—is indented below the definition

line. The body concludes with a return keyword followed by the return value.

When we call the function, the values we pass to it are assigned to those variables so that we can use them inside the function. Inside the function, we use a return statement to send a result back to whoever asked for it.

Calling our own function is no different from calling any other function (like built-in functions, or functions from a library). We can use it in conditionals, calculations, print statements, or anywhere else we need the value. For example:

if rush_hour_percentage(traffic_data[0]) < 10:

print('Day 1 had low rush hour traffic')

Day 1 had low rush hour traffic

Functions let us:

Build complex calculations from simpler, reusable pieces

Update calculations easily by changing the function definition in one place

Make code more readable by giving chunks of code meaningful names

Composing Functions#

Now suppose we want to write another function that calculates the total rush hour traffic across all days in our dataset.

Currently, the rush hour calculation (day_data[7] + day_data[8] + day_data[9])

is embedded inside rush_hour_percentage. If we want to use it in a new function,

we’d have to write it again, like this:

def total_rush_hour_traffic(traffic_data):

total = 0

for day in traffic_data:

total += day[7] + day[8] + day[9]

return total

But now if we need to change the definition of “rush hour”, say to include 6am as well, we’d have to update it in multiple places. Instead, we can split the definition of “rush hour” into its own function:

def rush_hour_traffic(day_data):

return day_data[7] + day_data[8] + day_data[9]

And now we can re-use this function in multiple places:

def total_rush_hour_traffic(traffic_data):

total = 0

for day in traffic_data:

total += rush_hour_traffic(day)

return total

def rush_hour_percentage(day):

return (rush_hour_traffic(day) / numpy.sum(day)) * 100

Now if we decide that rush hour should include 6am as well, we only need to update the rush_hour_traffic function definition in one place:

def rush_hour_traffic(day):

return day[6] + day[7] + day[8] + day[9]

All the functions that use rush_hour_traffic()—both total_rush_hour_across_days and rush_hour_percentage—will automatically use the new definition:

print('Total rush hour traffic across all days, including 6am:', total_rush_hour_traffic(traffic_data))

print('Rush hour percentage on first day, including 6am:', rush_hour_percentage(traffic_data[0]))

Total rush hour traffic across all days, including 6am: 155928.0

Rush hour percentage on first day, including 6am: 10.26803101653507

We don’t have to hunt through our code to find every place we wrote the old calculation.

Variable Scope

We often create variables inside of functions. For example, the daily_total variable in the rush_hour_percentage function.

We refer to these variables as local variables because they no longer exist once the function is done executing. If we try to access their values outside of the function, we will encounter an error:

print(daily_total)

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

NameError Traceback (most recent call last)

<ipython-input-1-eed2471d229b> in <module>

----> 1 print(daily_total)

NameError: name 'daily_total' is not defined

If we want to access a value outside of a function, we need to return it from the function.

Variables defined outside of any function are called global variables, and are accessible from anywhere in a program.

Tidying up#

Now that we know how to wrap bits of code up in functions, we can make our traffic visualization easier to understand.

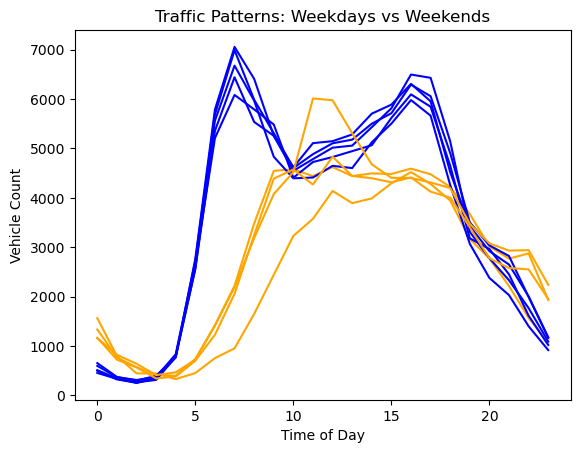

Let’s break out the logic we used before for determining if a day is a weekday into its own function:

def is_weekday(day):

return day[7] > 5000

This function takes a single day’s data and returns True if it’s a weekday (has heavy morning traffic at 7am) or False if it’s a weekend. Now we can use this function in our plotting code:

for day in traffic_data:

if is_weekday(day):

plt.plot(day, color='blue')

else:

plt.plot(day, color='orange')

plt.title('Traffic Patterns: Weekdays vs Weekends')

plt.xlabel('Time of Day')

plt.ylabel('Vehicle Count');

Notice how much clearer the if statement is now. Instead of if data[i, 7] > 5000:, we have if is_weekday(data[i]):. The function name is_weekday makes the intent of the condition immediately clear—we’re checking whether this day is a weekday. This makes the code more readable because anyone reading it can understand what we’re checking for, not just how we’re checking it. Even better, if we need to check if a day is a weekday elsewhere in our code, we can reuse this function. Then we don’t have to write the same code over and over again, or update it in multiple places if we want to change it.

Readable functions#

Consider these two functions:

def s(p):

a = 0

for v in p:

a += v

m = a / len(p)

d = 0

for v in p:

d += (v - m) * (v - m)

return numpy.sqrt(d / (len(p) - 1))

def std_dev(sample):

sample_sum = 0

for value in sample:

sample_sum += value

sample_mean = sample_sum / len(sample)

sum_squared_devs = 0

for value in sample:

sum_squared_devs += (value - sample_mean) * (value - sample_mean)

return numpy.sqrt(sum_squared_devs / (len(sample) - 1))

The functions s and std_dev are computationally equivalent (they

both calculate the sample standard deviation), but to a human reader,

they look very different. You probably found std_dev much easier to

read and understand than s.

As this example illustrates, both documentation and a programmer’s coding style combine to determine how easy it is for others to read and understand the programmer’s code. Choosing meaningful variable names and using blank spaces to break the code into logical “chunks” are helpful techniques for producing readable code. This is useful not only for sharing code with others, but also for the original programmer. If you need to revisit code that you wrote months ago and haven’t thought about since then, you will appreciate the value of readable code!

Challenge 1: Combining Strings

“Adding” two strings produces their concatenation:

'a' + 'b' is 'ab'.

Write a function called fence that takes two parameters called original and wrapper

and returns a new string that has the wrapper character at the beginning and end of the original.

A call to your function should look like this:

print(fence('name', '*'))

*name*

Solution

def fence(original, wrapper):

return wrapper + original + wrapper

Challenge 2: Return versus print

Note that return and print are not interchangeable.

print is a Python function that prints data to the screen.

It enables us, users, see the data.

return statement, on the other hand, makes data visible to the program.

Let’s have a look at the following function:

def add(a, b):

print(a + b)

Question: What will we see if we execute the following commands?

A = add(7, 3)

print(A)

Solution

Python will first execute the function add with a = 7 and b = 3,

and, therefore, print 10. However, because function add does not have a

line that starts with return (no return “statement”), it will, by default, return

nothing which, in Python world, is called None. Therefore, A will be assigned to None

and the last line (print(A)) will print None. As a result, we will see:

10

None

Challenge 3: Selecting Characters From Strings

If the variable s refers to a string,

then s[0] is the string’s first character

and s[-1] is its last.

Write a function called outer

that returns a string made up of just the first and last characters of its input.

A call to your function should look like this:

print(outer('helium'))

hm

Solution

def outer(input_string):

return input_string[0] + input_string[-1]

Challenge 4: Rescaling an Array

Write a function rescale that takes an array as input

and returns a corresponding array of values scaled to lie in the range 0.0 to 1.0.

(Hint: If L and H are the lowest and highest values in the original array,

then the replacement for a value v should be (v-L) / (H-L).)

Solution

def rescale(input_array):

L = numpy.min(input_array)

H = numpy.max(input_array)

output_array = (input_array - L) / (H - L)

return output_array

Challenge 5: Testing and Documenting Your Function

Run the commands help(numpy.arange) and help(numpy.linspace)

to see how to use these functions to generate regularly-spaced values,

then use those values to test your rescale function.

Once you’ve successfully tested your function,

add a docstring that explains what it does.

Solution

"""Takes an array as input, and returns a corresponding array scaled so

that 0 corresponds to the minimum and 1 to the maximum value of the input array.

Examples:

>>> rescale(numpy.arange(10.0))

array([ 0. , 0.11111111, 0.22222222, 0.33333333, 0.44444444,

0.55555556, 0.66666667, 0.77777778, 0.88888889, 1. ])

>>> rescale(numpy.linspace(0, 100, 5))

array([ 0. , 0.25, 0.5 , 0.75, 1. ])

"""

Challenge 6: Defining Defaults

Rewrite the rescale function so that it scales data to lie between 0.0 and 1.0 by default,

but will allow the caller to specify lower and upper bounds if they want.

Compare your implementation to your neighbor’s:

do the two functions always behave the same way?

Solution

def rescale(input_array, low_val=0.0, high_val=1.0):

"""rescales input array values to lie between low_val and high_val"""

L = numpy.min(input_array)

H = numpy.max(input_array)

intermed_array = (input_array - L) / (H - L)

output_array = intermed_array * (high_val - low_val) + low_val

return output_array

Challenge 7: Variables Inside and Outside Functions

What does the following piece of code display when run — and why?

f = 0

k = 0

def f2k(f):

k = ((f - 32) * (5.0 / 9.0)) + 273.15

return k

print(f2k(8))

print(f2k(41))

print(f2k(32))

print(k)

Solution

259.81666666666666

278.15

273.15

0

k is 0 because the k inside the function f2k doesn’t know

about the k defined outside the function. When the f2k function is called,

it creates a local variable

k. The function does not return any values

and does not alter k outside of its local copy.

Therefore the original value of k remains unchanged.

Beware that a local k is created because f2k internal statements

affect a new value to it. If k was only read, it would simply retrieve the

global k value.

Challenge 8: Mixing Default and Non-Default Parameters

Given the following code:

def numbers(one, two=2, three, four=4):

n = str(one) + str(two) + str(three) + str(four)

return n

print(numbers(1, three=3))

what do you expect will be printed? What is actually printed? What rule do you think Python is following?

1234one2three41239SyntaxError

Given that, what does the following piece of code display when run?

def func(a, b=3, c=6):

print('a: ', a, 'b: ', b, 'c:', c)

func(-1, 2)

a: b: 3 c: 6a: -1 b: 3 c: 6a: -1 b: 2 c: 6a: b: -1 c: 2

Solution

Attempting to define the numbers function results in 4. SyntaxError.

The defined parameters two and four are given default values. Because

one and three are not given default values, they are required to be

included as arguments when the function is called and must be placed

before any parameters that have default values in the function definition.

The given call to func displays a: -1 b: 2 c: 6. -1 is assigned to

the first parameter a, 2 is assigned to the next parameter b, and c is

not passed a value, so it uses its default value 6.

Readable Code

Revise a function you wrote for one of the previous exercises to try to make the code more readable. Then, collaborate with one of your neighbors to critique each other’s functions and discuss how your function implementations could be further improved to make them more readable.

Keypoints

Define a function using

def function_name(parameter).The body of a function must be indented.

Call a function using

function_name(value).Numbers are stored as integers or floating-point numbers.

Variables defined within a function can only be seen and used within the body of the function.

Variables created outside of any function are called global variables.

Within a function, we can access global variables.

Variables created within a function override global variables if their names match.

Use

help(thing)to view help for something.Put docstrings in functions to provide help for that function.

Specify default values for parameters when defining a function using

name=valuein the parameter list.Parameters can be passed by matching based on name, by position, or by omitting them (in which case the default value is used).

Put code whose parameters change frequently in a function, then call it with different parameter values to customize its behavior.